Astronomers detect a stellar explosion so violent it could destroy the atmosphere of planets like Earth

The first extrasolar coronal mass ejection from the red dwarf star StKM 1-1262 has been detected. This explosion raises questions about the habitability of exoplanets, as it could strip them of their atmospheres.

For the first time, astronomers have captured a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) originating from a star other than our Sun. The star in question is the active red dwarf StKM 1-1262, located 40 light-years away—very close in cosmic terms.

A coronal mass ejection (CME) is a massive ejection of magnetized plasma that contributes significantly to space weather. In our solar system, these explosions cause auroras, but on other worlds they have the potential to erode and completely destroy planetary atmospheres.

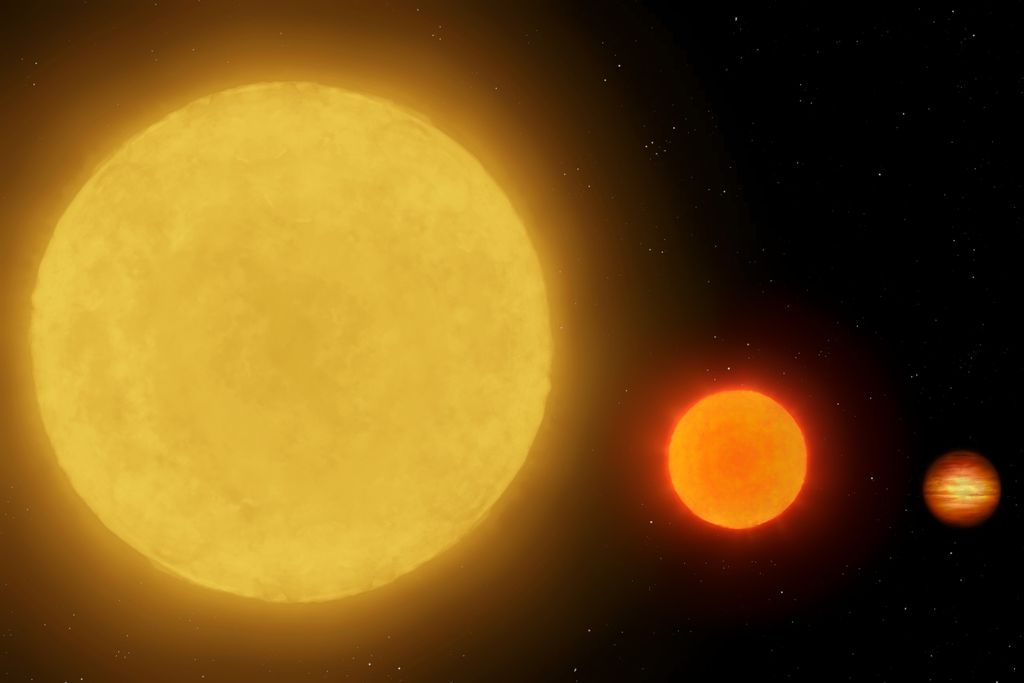

StKM 1-1262 is a fascinating and violent star that has approximately half the mass of the Sun, spins 20 times faster, and has a magnetic field 300 times more intense than the global field of our Sun.

Detecting an extrasolar CME has been a historic challenge for astronomy, since previously we only intuited its existence through indirect methods, such as changes in ultraviolet light or X-rays, but it was not confirmed that the plasma escaped completely.

However, these “explosions” produce a shock wave that, as it travels through space, emits a key signal , a radio burst known as a Type II burst , which is proof that the material has escaped the stellar magnetic field.

A plasma scream in the cosmos

The radio burst was detected by the LOFAR (Low Frequency Array) radio telescope, thanks to its low-frequency sweep across the northern hemisphere. The eruption lasted approximately two minutes and traveled at an astonishing supersonic speed of 2,400 kilometers per second.

News: Astronomers confirmed the first coronal mass ejection ever seen on a star beyond the Sun.

— Seekers Of The Cosmos (@SeekersCosmos) November 12, 2025

It erupted from the red dwarf StKM 1-1262, about 130 light-years away, powerful enough to strip a nearby planets atmosphere. pic.twitter.com/LVd4CTDVDo

To put this into perspective, only about 5% of the fastest ejections observed on the Sun reach or exceed that speed . Although the Sun also has coronal mass ejections (CMEs), the magnitude and rate of these events in red dwarfs can be far more extreme.

In addition to LOFAR, the XMM-Newton observatory was crucial in determining stellar conditions , such as coronal temperature. As it was a super-Alfenic shock, the detection also allowed scientists to establish an upper limit of 19 Gauss for the coronal magnetic field at three stellar radii.

The signal observed in StKM 1-1262 matches the fundamental plasma emission properties of a Type II solar flare, which is evidence that the hot plasma was undoubtedly released into the star's interplanetary medium.

Life in the danger zone

This finding is fundamental because most of the potentially habitable exoplanets we have found orbit red dwarfs , and in this type of star, which is cooler, the habitable zone (where liquid water could exist) is much closer to the star.

A planet in the habitable zone of StKM 1-1262 would be exposed to much more frequent and energetic CME impacts than Earth , but the pressure generated by this type of explosion could be devastating for any nearby world.

Called ram-pressure , this phenomenon could compress a planet's magnetosphere down to its surface, even if the planet has a robust magnetic field like Earth's. This means that, despite being in the "right zone," the planet could lose its atmosphere .

The density of the ejected plasma is estimated to be over 300 million particles per cubic centimeter. This figure is ten times greater than what is usually simulated for CME impacts on exoplanets, reinforcing the gravity of this event.

New limits in the search for worlds

Thanks to this detection, scientists are no longer limited to extrapolating the rates and kinematics of solar CMEs to other stars, but have been able to establish the first empirical observational limits on the true impact of CMEs on other stellar systems.

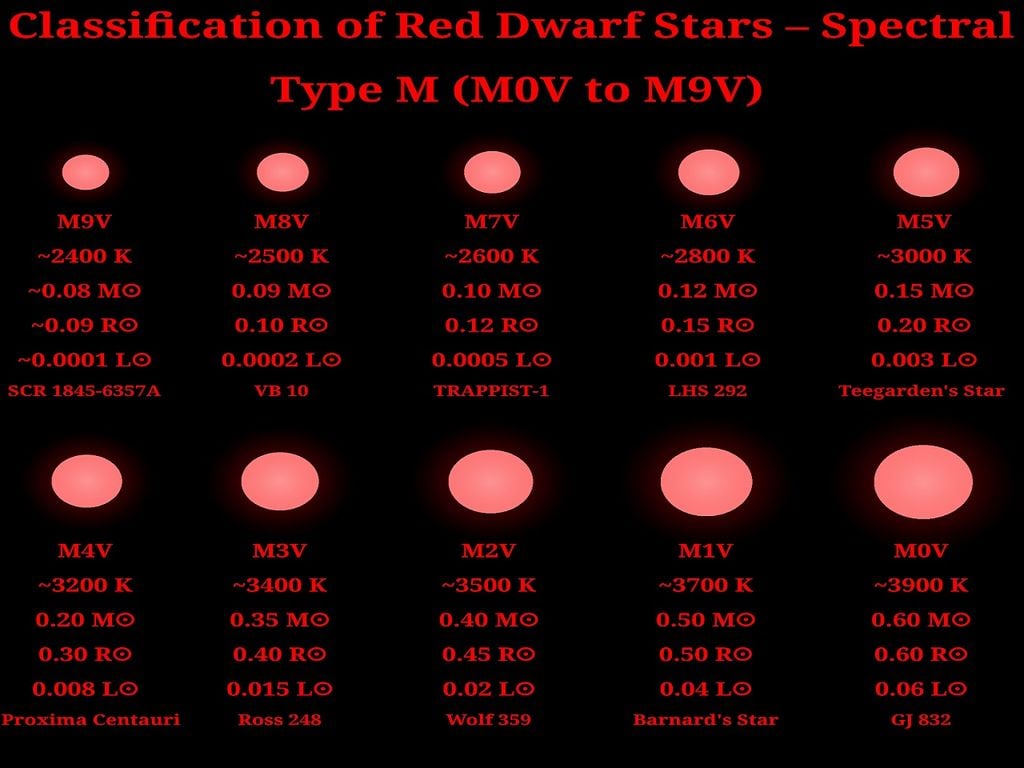

The study suggests that the rate of such luminous events in M dwarfs (types M0 to M6) is low , approximately one thousandth per day per star. This implies that, although rare, these super-fast outbursts are consistent with the solar rate of Type II stars.

This pioneering work confirms that the space weather around smaller stars can be even more extreme than imagined , and the finding opens a new observational frontier for understanding eruptions and the future of habitability in the galaxy.

Detection with LOFAR, an array of antennas that captures low frequencies, demonstrates its power to detect stellar explosions. Success in this field lays the groundwork for future studies with instruments such as the upcoming Square Kilometre Array (SKA).