The Death of the Sun: A Neighbouring Red Giant Reveals the Fate of Our Star

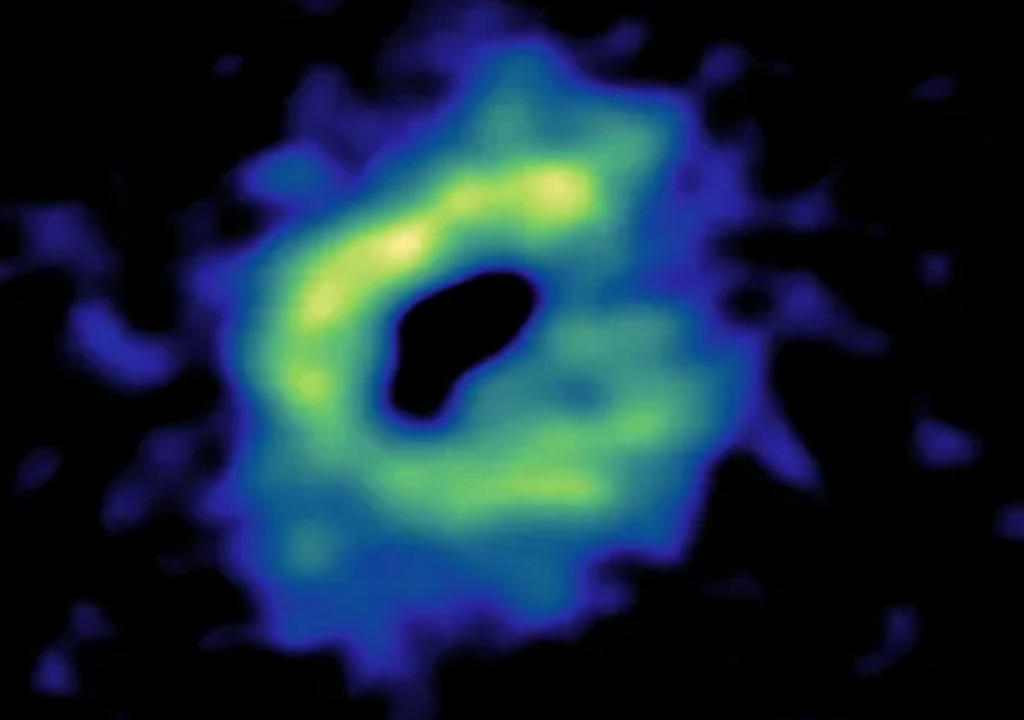

An international team observed the red giant W Hydrae, located about 320 light-years away, with unprecedented clarity. By simultaneously capturing 57 molecules, ALMA revealed 57 “faces” (corresponding to different layers) of its turbulent atmosphere.

Never before have we observed the atmosphere of a dying star beyond our Sun with such clarity. The star is called W Hydrae (W Hya), located about 320 light-years away, and it is at an advanced stage of its evolution, already a red giant.

A new study combined images from the ALMA radio telescope with optical observations from the VLT (ESO), revealing a turbulent and chemically diverse landscape.

57 “faces” of a single star

The achievement can be summed up in a number: 57. By observing 57 molecular spectral lines simultaneously, astronomers obtained 57 “faces” of the same star. Each molecule acts as a filter, highlighting a different layer because it forms and “survives” under specific conditions of temperature, density, and collisions.

W Hydrae was chosen as a natural laboratory because it is one of the nearest and brightest old red giants in radio and infrared. Observations explored frequencies between 250 and 268 GHz, allowing researchers to create an exceptional chemical inventory at this scale, published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

The resolution achieved by ALMA, around 17 to 20 milliarcseconds, allowed astronomers to resolve the stellar disc and track gas very close to the “surface,” where the star begins to lose mass.

The diversity of W Hydrae’s faces helps understand the physics of our system

At this scale, arcs and columns appear, suggesting a constantly reshaping environment. In some lines, the atmosphere extends over several times the star’s size. If W Hydrae were at the centre of our solar system, its outer layers would encompass Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars.

The diversity of the “faces” also serves as a guide to interpreting the physics of the system. Some spectral lines reveal almost circular layers, while others highlight an elongated tail or asymmetric regions where the gas appears compressed by shock waves.

Signals are also observed appearing in absorption on the stellar disc, while others emerge as bright spots directly at the surface, indicating very hot and dynamic layers. The final image is anything but uniform.

One of the most intriguing findings is that the stellar wind is not a simple outflow. The data show a combination of movements: gas expelled at speeds of up to around 10 km/s, but also material falling back into the upper layers at speeds of 13 km/s. This back-and-forth motion suggests an atmosphere shaped by pulsations, shocks, and convection, creating alternating zones of outflowing and inflowing gas.

This dynamic helps explain why mass loss in AGB stars remains a complex problem. The star seems to “attempt” to expel material, but part of it returns, in an unstable balance that depends on the rhythm of the pulsations and how the dust forms and is then accelerated by radiation.

From gas to dust almost in real time

ALMA’s observations were compared with images from the SPHERE instrument on the VLT, obtained just nine days earlier. This short interval allowed researchers to link regions rich in specific molecules to the dust clouds observed in visible light.

The configuration observed suggests that certain species appear exactly where the dust is densest, supporting the idea that they participate in the very first stages of nucleation, as molecules and atoms begin to assemble into dust grains.

Other molecules appear to overlap only in specific regions and may be linked to collision-driven chemical reactions. Hydrogen cyanide (CH₃N), however, is found very close to the star, consistent with collision-induced chemistry, but it does not act as a direct tracer of areas dominated by freshly formed dust.

Distinguishing these behaviours goes far beyond a simple chemical detail. It allows scientists to refine models that determine where the stellar wind becomes efficient and under which conditions material can escape. Ultimately, it is this ejected material that enriches the interstellar medium with elements and compounds produced within stars.

W Hydrae thus offers a glimpse into the distant future of our own Sun. The Sun is expected to enter a similar phase in around 5 billion years.

References of the news:

Ohnaka, K., Wong, K. T., Weigelt, G., & Hofmann, K. H. (2025). High-angular-resolution ALMA imaging of the inhomogeneous dynamical atmosphere of the asymptotic giant branch star W Hya-SiO, H2O, SO2, SO, HCN, AlO, AlOH, TiO, TiO2, and OH lines. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 704, A18.