The Sun Has an Expiration Date, but Earth Will Disappear Much Earlier: NASA Explains the Dramatic Reason

Our Sun, which today sustains life on Earth, also has an expected end in about 5 billion years; its evolution will turn it into a dying star.

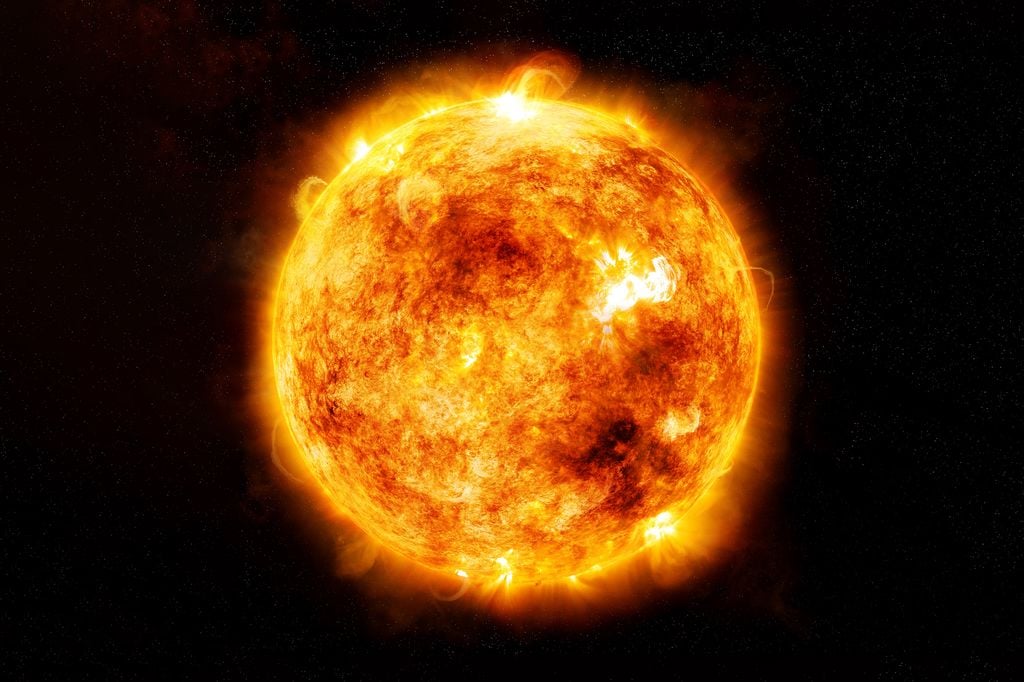

The Sun, a G2V-type star, is currently in the stable phase known as the main sequence. For about 4.5 billion years, it has fused hydrogen into helium in its core, generating the energy that maintains its luminosity and the balance between internal pressure and the gravity attempting to collapse it.

Every second, the Sun transforms more than four million tons of matter into energy, a figure that fuels all its electromagnetic radiation. Thanks to this process, its brightness and size remain stable in a dynamic equilibrium that has allowed life to develop on Earth.

However, the Sun is not eternal. The amount of hydrogen in its core is finite, and at some point it will run out. When that happens, nuclear fusion will shift to outer layers, altering the star’s current stability and beginning its slow transformation.

Although this change may seem imminent on the cosmic scale, five billion years still remain. According to NASA, the Sun has only consumed about half of its nuclear fuel, so it still has a long life ahead as a main-sequence star.

Earth, however, will not survive the entire process, as long before the Sun’s final stage, changes in its luminosity and temperature will make it impossible to maintain liquid oceans and a stable atmosphere, slowly sealing our planet’s fate.

The Beginning of the End: The Sun Becomes a Red Giant

When the central hydrogen runs out, gravity will compress the Sun’s core, increasing its temperature while the outer layers begin to expand. At this point, the Sun will enter its red giant phase, a state cooler on the surface but enormous in size.

During this expansion, its diameter will reach the current orbit of Earth, engulfing Mercury and Venus in the process. Although Earth might escape being fully swallowed, its proximity to the solar plasma would raise temperatures high enough to vaporize its oceans and crust.

In the core, temperatures will reach 100 million degrees, allowing the fusion of helium into carbon and oxygen, a process known as the “triple-alpha” reaction, which will prolong the Sun’s life for a few hundred million years but will not stop its final destiny.

Once the helium is also depleted, the core will be composed of degenerate carbon and oxygen, unable to continue fusion. The Sun will expel its outer layers in a bright stellar wind, forming a beautiful planetary nebula that will shine for a few thousand years.

A White Dwarf: The Heart That Survives

When the outer layers dissipate, what remains of the Sun will be a sphere the size of Earth but with less than half its original mass—an object known in astronomy as a white dwarf. This dead star will no longer produce nuclear energy, shining only from the remaining heat of its former life.

White dwarfs are extremely dense objects: a teaspoon of their material would weigh several tons on Earth. Their surface temperature will exceed 100,000 °C, although over time it will cool slowly, reducing its brightness until it becomes invisible to the naked eye.

In this final stage, the Sun will not destroy the galaxy nor produce a supernova, because it does not have enough mass. It will simply fade away slowly over trillions of years, becoming a hypothetical black dwarf—a cold, silent relic of its former brilliance.

By then, the solar system will no longer exist as we know it. The outer planets will drift or be expelled due to the Sun’s mass loss, and Earth will be nothing more than metallic dust in interstellar space.

The Solar Legacy and a Vision of the Future

Although the Sun’s end may seem bleak, this evolution is a natural part of a cosmic cycle in which the expelled material will form new atoms that could someday become part of other stars or planets, restarting the history of the cosmos with the same elements that make us who we are today.

Scientists study the Sun’s destiny by observing similar stars in different evolutionary stages, thanks to missions such as the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), SOHO, and the Parker Solar Probe, which allow us to understand how magnetic fields, eruptions, and luminosity change over time.

Knowing that the Sun has a defined cycle does not imply an immediate threat, but rather a reminder of our place in the Universe. Stellar transformations are not catastrophes, but transitions that ensure the renewal of matter and the continuity of cosmic life.

Ultimately, the Sun teaches us that even stars must die so that others may be born, leaving behind the promise of new worlds to come—and the quiet solitude of a universe that knows nothing of “humans.”