This Is the 27-Kilometer Machine That Recreates the Beginning of the Universe and Could Find the God Particle

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world’s largest scientific instrument, recreates high-energy collisions to search for new fundamental particles, such as the mysterious Higgs boson.

At the heart of fundamental physics, CERN houses the largest and most complex scientific instrument: the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). A circular tunnel 27 kilometers in circumference and a colossal engineering feat, with the mission of probing the structure of the particles that make up the universe.

The LHC acts as a subatomic racetrack, propelling charged particles—such as protons—to speeds close to that of light. This is achieved using electromagnetic fields and radiofrequency systems that gradually increase their energy.

After reaching this maximum speed, the particles are forced to collide head-on, allowing the energy of both beams to combine. Although the energy of a single proton is tiny in everyday terms—similar to a pin dropping two centimeters—it is concentrated on an infinitesimal scale.

This extreme concentration of energy accomplishes something astonishing: it recreates the conditions that existed in the universe just a fraction of a second after the Big Bang. Einstein’s famous equation, E=mc², reminds us that this collision energy is instantly transformed into matter in the form of new particles.

By studying these collisions, scientists can observe massive particles that exist only for an instant, such as the Higgs boson or the top quark. These discoveries, which occur in the blink of an eye, drastically increase our understanding of matter and the mysterious origin of the cosmos.

The Search for the “God Particle”

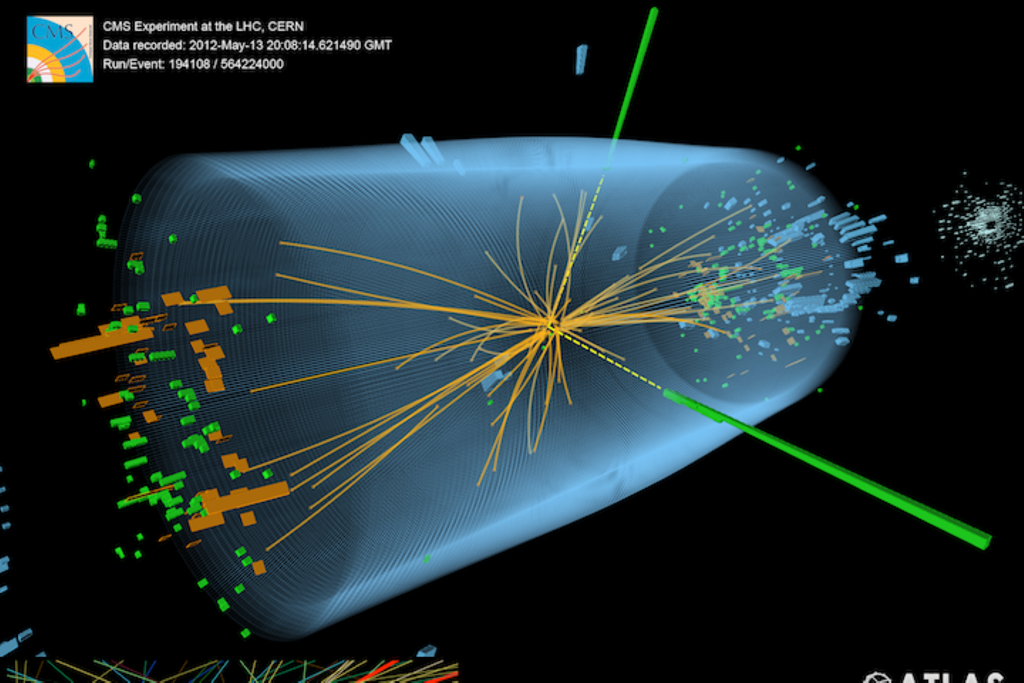

The Higgs boson is the missing piece of the Standard Model of particle physics, first proposed in 1964, and its existence was confirmed at CERN by the ATLAS and CMS collaborations in 2012. Its discovery placed electroweak theory on solid experimental ground.

This particle, often called the “God particle” in popular culture, is actually a ripple in an invisible quantum field that fills the entire universe: the Higgs field. Elementary particles acquire their mass by interacting with this field, as if they were vehicles experiencing friction as they move along a road.

Detecting the Higgs boson is a monumental challenge, often compared to searching for a needle in a cosmic haystack. It is produced only about once in every billion collisions inside the LHC, and its lifetime is so short that it decays almost instantly into lighter particles.

Since the boson cannot be observed directly, scientists precisely measure the products of its decay. By statistically analyzing enormous volumes of data, they search for a “bump” in invariant-mass histograms, which confirms its existence indirectly, with a certainty known as “five sigma.”

Extreme Engineering

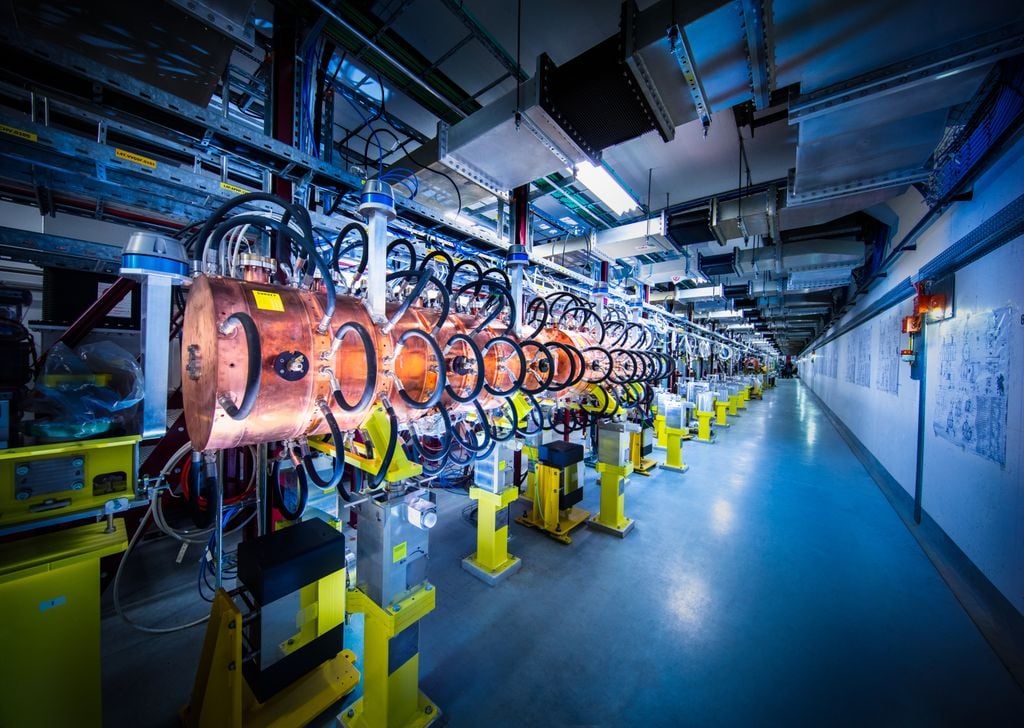

Imagine wanting a pendulum to swing higher not by giving it a big push, but many small ones; something similar happens in a circular accelerator like the LHC, where protons complete lap after lap, receiving a boost of energy each time through structures called radiofrequency cavities.

To keep protons traveling at speeds close to light inside a 27-kilometer ring, extremely powerful magnetic fields are needed. These superconducting magnets—cooled by cryogenic systems—focus the beams and bend their trajectory with precision, making their control essential.

Engineering is fundamental at CERN; in fact, the organization employs more engineers and technicians than research physicists. They are responsible for developing and building these gigantic, complex machines, which require unprecedented precision across millions of components.

The speed reached means that each proton acquires an energy of 6.5 tera-electronvolts (TeV), generating collisions of 13 TeV. Although this is a tiny amount of energy at human scale, when concentrated at a subatomic point, it achieves energy densities comparable to those of the early universe.

The Future and the Search for New Particles

The main objective of physics at CERN is to answer the questions that the Standard Model, despite its success, still cannot resolve. Scientists are searching for new particles and phenomena that explain the 95% of the universe’s mass and energy that remains unknown in the form of dark matter and dark energy.

Among the greatest mysteries that persist are the nature of dark matter and the reason why gravity is so weak compared to the other three fundamental forces. The Higgs boson, through its interactions with the rest of the particles, becomes a crucial laboratory for this new physics.

One of the most promising searches is to see whether the Higgs boson decays into “invisible” particles—those that do not interact with the electromagnetic, strong, or weak forces. If this happens, it could be the first direct evidence leading to the discovery of the elusive dark-matter particles.

The journey is only beginning, and research on the Higgs explores whether it is a standalone particle or part of a more complex “Higgs sector.” To continue pushing the boundaries of knowledge, the High-Luminosity LHC and future accelerators planned for after 2040 are already underway.