The strnagest moon in the solar system is bright yellow - and it’s not just for show

Jupiter’s moons are full of weird surprises, but one of them has stood out for years. A 'true colour' view and a few brutal stats explain why Io keeps stealing the spotlight.

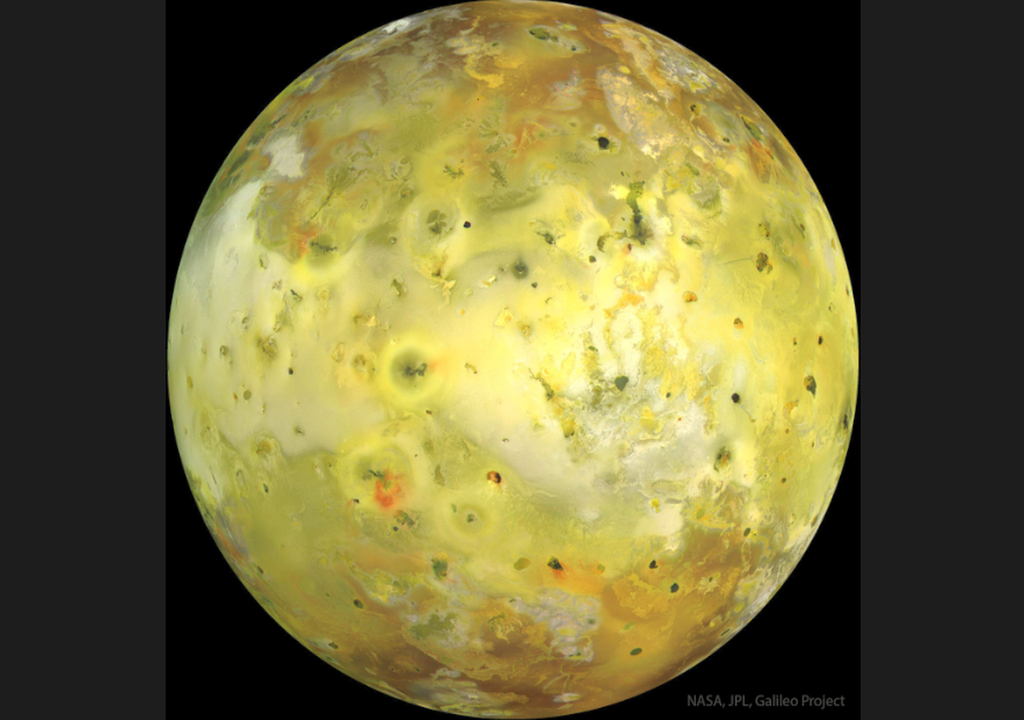

Most moons you picture are basically big, grey, dented rocks that just… sit there. Io is not that moon. It’s the sort of world that looks like it’s been attacked with a highlighter pen, and then somehow got even more dramatic once scientists started properly clocking what was going on.

Here’s the backstory: Io is Jupiter’s closest big moon, first spotted by Galileo Galilei back in 1610. It even started life with a very literal name — “Jupiter I” — before it was renamed after Io from Greek mythology.

A moon that won’t sit still

Size-wise, it’s roughly 3,600 km across, making it the third largest of Jupiter’s moons. But what really gives it away is the surface: huge plains, big mountain chains, and a weird lack of impact craters, which points to a geologically young face - like it’s been constantly resurfaced.

And “constantly” isn’t an exaggeration. Io has over 400 active volcanoes, making it the most geologically active object in the Solar System. Some eruptions throw up plumes of sulphur and sulphur dioxide that can reach about 500 km above the surface - basically space-level fireworks, minus the fun bit when you’re trying to study them.

It’s not just lava either. Io’s surface is dotted with more than 100 mountains, pushed up by intense compression in its crust, and some peaks are taller than Mount Everest. So it’s got the chaos of volcanoes and the muscle of serious tectonics - on a moon.

Where the colour comes from

That loud yellow look? It’s largely down to sulphur and sulphur dioxide on the surface, alongside molten silicate rock from all that volcanism. The engine behind it is tidal heating: Jupiter’s gravity (plus nudges from neighbouring moons) flexes Io like a stress ball, generating heat inside until material forces its way out.

A “true colour” mosaic from NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, taken on 3 July 1999, tried to show how Io would look to the average human eye — and it’s every bit as striking as you’d hope. Galileo kept orbiting Jupiter until the mission ended in September 2003, so it had time to watch Io’s surface keep reinventing itself.

And if you’re wondering why anyone cares beyond the colour, Io is basically a natural lab for how tidal forces can heat and reshape worlds - a clue for understanding volcanism across the Solar System - and maybe beyond.

Reference of the news: Global image of Io (true colour), NASA, August 1999; Io (moon), accessed January 2026.