The Women Who Were Paid To Count Stars and Ended Up Discovering How the Universe Works

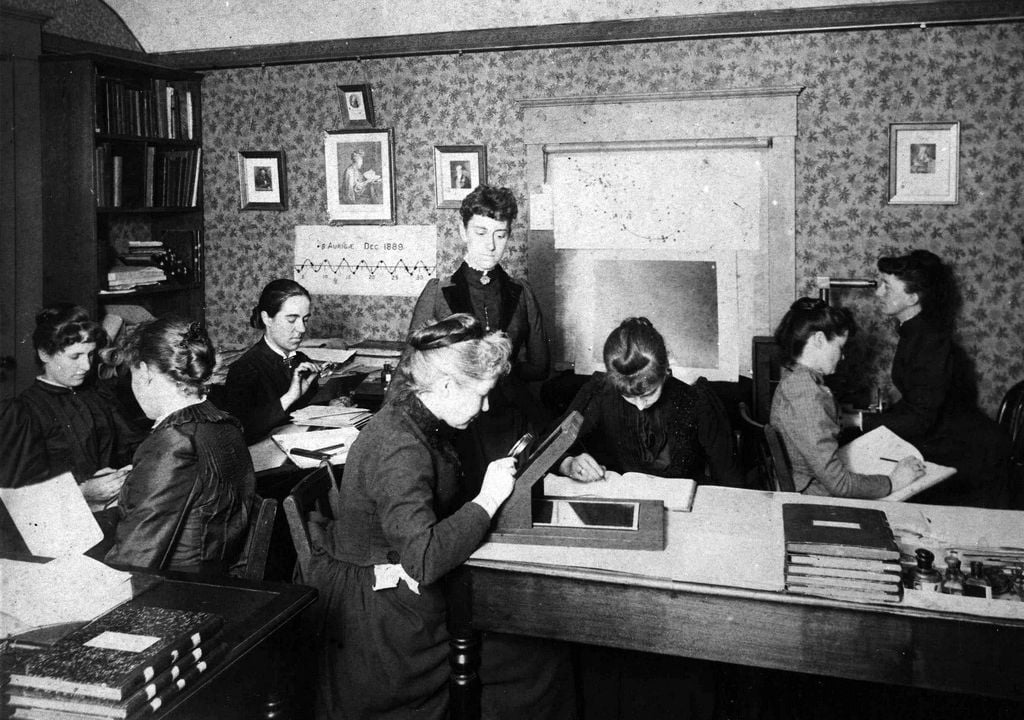

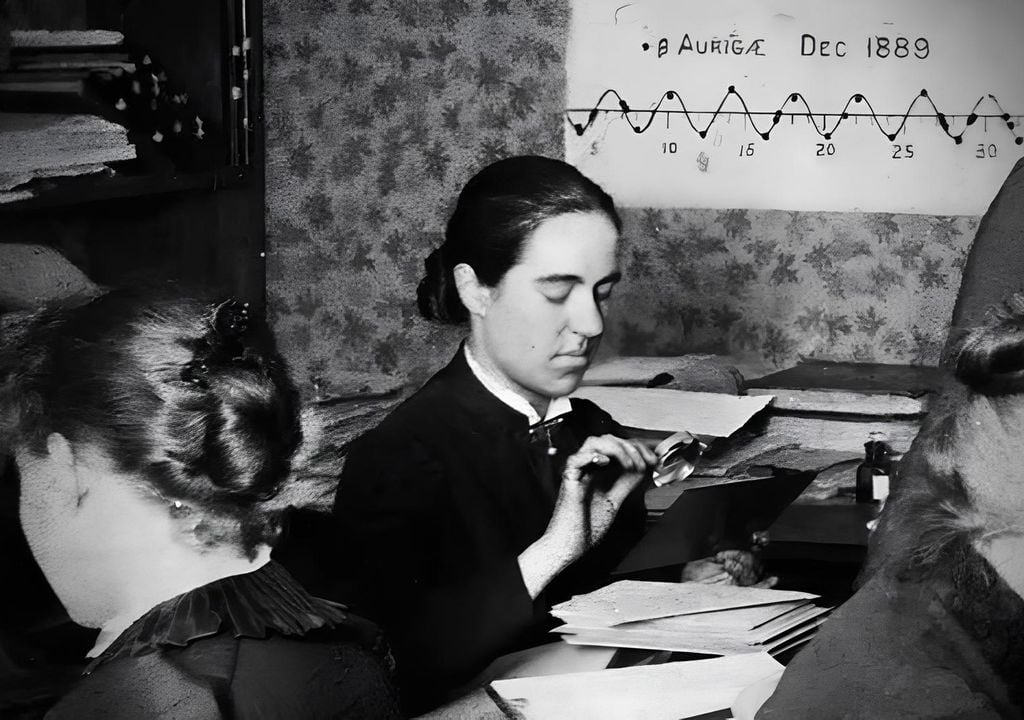

A group of brilliant women worked at the Harvard Observatory classifying stars for minimum pay, unaware that their calculations would reveal the structure of the cosmos, make it possible to measure astronomical distances, and lay the foundations of modern astrophysics.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a group of women worked at the Harvard College Observatory under the direction of Edward Charles Pickering. They were known as the “Harvard computers”—or, less kindly at the time, “Pickering’s harem”—because they carried out meticulous tasks of star calculation and cataloging for very low pay.

However, these young women were not just counting stars: they built a team that forever changed the way we understand the cosmos.

Thanks to their work, the modern stellar classification system (OBAFGKM) was established, a fundamental method for measuring distances in the universe was discovered, and pioneering ideas on the chemical composition of stars were formulated. Their work defined twentieth-century astronomy and remains the foundation of modern astrophysics.

This is the story and remarkable legacy of the central figures of this quiet revolution.

Williamina Fleming: The Pioneer Who Opened the Way

Williamina Fleming (1857–1911), a Scottish immigrant who arrived in Boston under difficult circumstances (her husband abandoned her while she was pregnant), became a key figure at the Harvard Observatory.

She was initially hired as a domestic worker, but Pickering, impressed by her intelligence and discipline, brought her into the observatory.

Fleming supervised the team of computers and developed one of the first stellar classification systems. She cataloged more than 10,000 stars, identified variable stars and novas, and in 1888 discovered the famous Horsehead Nebula. She also produced the Draper Catalogue, the foundation of modern spectral classification.

Horsehead Nebula, located 1,500 light-years from Earth in the constellation Orion. (Photo: Bill Snyder) pic.twitter.com/lFIBe3zbvr

— CSIC (@CSIC) September 15, 2016

Her work laid the foundations for what her colleagues would later refine.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt: The Woman Who Measured the Universe

The American astronomer Henrietta Leavitt (1868–1921) made one of the most important discoveries in astronomy: the relationship between the period and luminosity of Cepheids, regularly pulsating variable stars.

By studying thousands of stars in the Magellanic Clouds, Leavitt found that the longer the period of a Cepheid, the greater its absolute luminosity. This period–luminosity law became a cosmic measuring tool: if the period of the star is known, its true luminosity can be deduced and, by comparing it to its apparent brightness, its distance can be calculated.

This method allowed Edwin Hubble, for example, to confirm that the Andromeda Nebula was actually another galaxy, and later to measure the expansion of the universe. Without Leavitt, there would be no modern cosmology.

Annie Jump Cannon: The Architect of the OBAFGKM System

The American Annie Jump Cannon (1863–1941) was the mind that gave final shape to the stellar classification system used today. A star’s spectrum works like its “fingerprint,” allowing its elements, temperature, and other properties to be identified when its light is broken down.

But the existing classification was confusing and redundant, so Cannon reduced it to seven fundamental types: O, B, A, F, G, K, M, arranged by temperature. This system, adopted worldwide in 1922, remains in use because it clearly reflects stellar physics: the hottest stars are type O and the coolest are type M.

Famous for her speed and precision, Cannon classified more than 350,000 stars, an unbeatable record for the era. She also opened doors for women in astronomy, becoming the first woman to receive an honorary degree from Oxford and to chair the International Astronomical Union.

Antonia Maury: An Original and Inspiring Mind

The New Yorker Antonia Maury (1866–1952) contributed a more detailed and complex view of stellar spectra. Although her classification system was not widely adopted at first because it was too sophisticated for the standards of the time, it contained ideas that were later recognized as fundamental.

Maury described spectral lines with great precision, allowing astronomers to identify spectroscopic binary stars—systems that can only be distinguished through shifts in their absorption lines—and study their orbits.

Her detailed analysis directly influenced the later work of Ejnar Hertzsprung (the Danish astronomer known for creating a diagram that relates stellar luminosity to color), who publicly praised the quality and depth of her observations.

Cecilia Helena Payne: The Woman Who Discovered What Stars Are Made of

Cecilia Payne (1900–1979) arrived at Harvard a few years later, but her work was directly supported by the classifications compiled by Cannon and the data collected by Fleming, Maury, and Leavitt.

In 1925, this legendary British astronomer demonstrated that stars are composed mainly of hydrogen and helium, contradicting the prevailing belief that they had a composition similar to Earth.

Her doctoral thesis, regarded as one of the most brilliant in the history of physics, established the foundations of modern astrophysics. She and her colleagues did not just count stars: they taught us how to interpret them.