‘A rare killer of the young’, or so we thought: researchers reveal reality of 1918 flu pandemic

Did the Spanish flu selectively lay low the young, fit, and healthy? Or was this a myth created and perpetuated by a society that lacked scientific evidence and a more open, inclusive view of humanity?

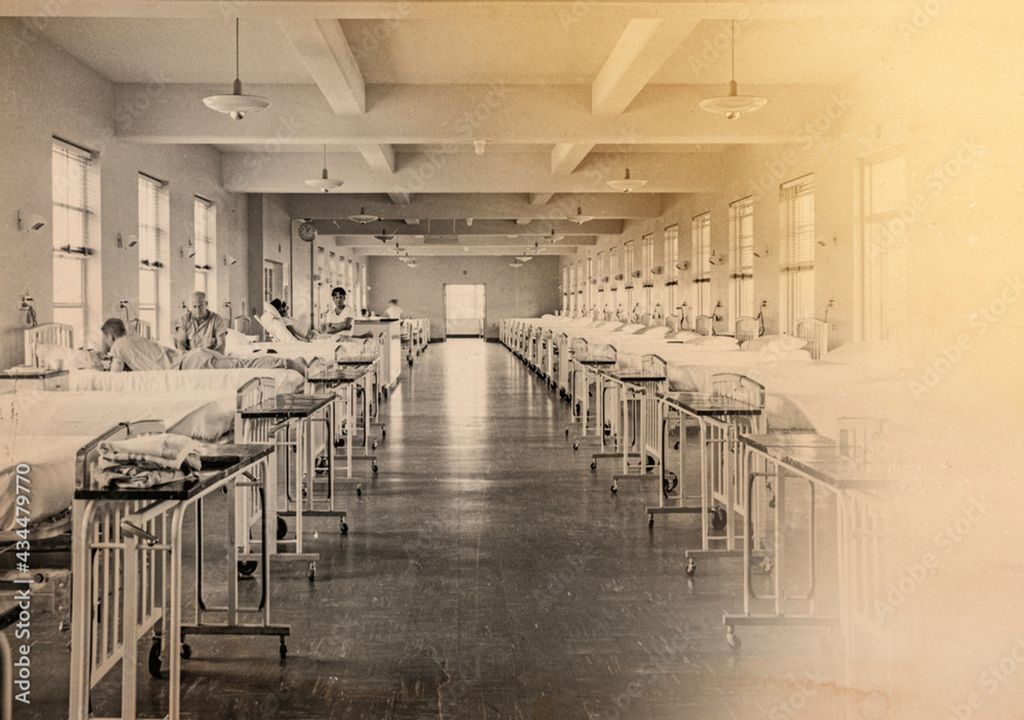

Researchers used skeletal remains to highlight the reality of the global influenza flu pandemic (or "Spanish flu") of 1918. The findings from the study — published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences — revealed that individuals with weak bone structures were more likely to be susceptible to the Spanish flu.

These findings contradict historical accounts, which posit that the influenza virus laid low the young and healthy and the old and frail. This research highlights the value of looking back in retrospect at old historical documents that may propound myth instead of truth.

Spanish flu

The Spanish flu was a severe influenza epidemic from 1918 to 1919. It is regarded by many as one of the most devastating pandemics in contemporary history. The pathogen that brought about the Spanish flu was a form of H1N1 influenza A virus. Although the specific origins of the Spanish flu are unknown, it is considered to have emerged in the United States or East Asia.

The term Spanish flu is a misnomer. It got that moniker since Spain, a neutral country amid World War I, reported widely on the outbreak of flu, while many other countries downplayed the pandemic's scope due to wartime censorship. This generated a sense that the flu was especially prevalent in Spain.

Estimates of the number of fatalities from the Spanish flu differ greatly due to the absence of reliable statistics at the time. It is thought that around 50 million people lost their lives to the Spanish flu, though this figure could

Study findings

The researchers turned to the Cleveland Museum of Natural History's Hamann-Todd Human Osteological Collection, which safeguards a repository of human skeletons that date to more than 3,000 years old.

In the present study, Assistant Professor of Anthropology at McMaster University, Amanda Wissler, and colleagues analysed the bones of 369 people who died before and during the 1918 Spanish flu. She was looking for porous lesions on the shinbones that might be caused by infection, stress, trauma, or poor nutrition.

Wissler and colleagues found that those individuals with weaker bone structures (including those with such lesions) were 2.7 times more likely to have perished during the 1918 flu outbreak.

Towards more effective public health interventions

It's critical to remember that the study has some limitations, including the small number of study specimens, all of which, came from Cleveland which may not accurately represent national trends. Nonetheless, the study emphasises the importance of nuanced public health messages and recognising that every individual is equally vulnerable during pandemics.

Understanding the characteristics that increase a person's vulnerability to severe disease or death might help drive resource allocation and public health interventions in future pandemics, eventually benefiting society as a whole.