How Big Can A Planet Grow? JWST Finds A Clue In Sulfur

New chemical measurements from a distant star system shed light on how massive gas giants form.

Scientists have detected hydrogen sulfide in the atmospheres of three massive exoplanets orbiting the young star HR 8799, marking the first time the molecule has been identified in planets observed through direct imaging. The measurement, made with NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, provides new evidence that these very large gas giants can form the same way Jupiter did: by accumulating solid material.

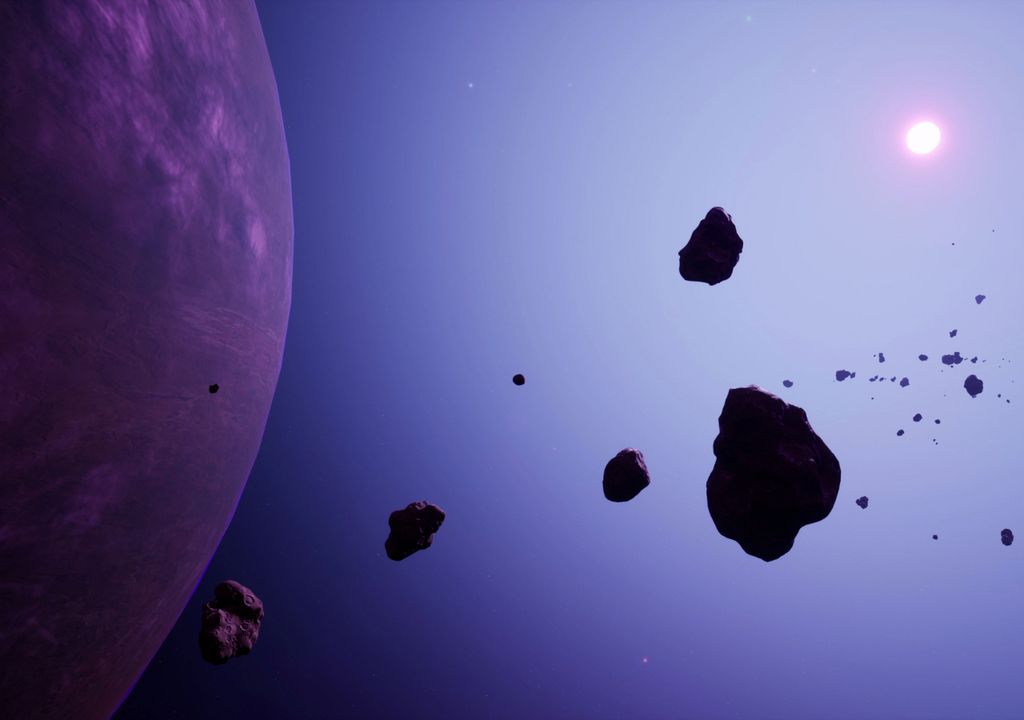

Located about 130 light-years from Earth, the HR 8799 system contains four known planets, each several times the mass of Jupiter. Since their discovery in 2008, these bodies have become key targets for studying young giant worlds because they can be observed directly, rather than inferred from subtle changes in their host star's motion.

In the new study, published in Nature Astronomy, researchers used Webb's Near Infrared Spectrograph to analyze infrared light from three of the planets: HR 8799 c, d, and e. The spectra revealed water vapor, methane, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide. From these measurements, the team derived the abundances of carbon, oxygen, and sulfur in each atmosphere.

The results showed that all three planets are enriched in these heavier elements relative to their host star, by factors of roughly two to nine.

What the Chemistry Reveals

Giant planets can form through two main pathways. In one, a region of a protoplanetary disk collapses rapidly under gravity, producing a planet whose composition closely resembles that of its star. In the other, a solid core assembles first from rock and ice before attracting a thick envelope of gas in a slower, bottom-up process that can concentrate heavier elements in the atmosphere.

Carbon and oxygen alone are not decisive, since both can be incorporated through gas accretion. Sulfur provides a stronger constraint. In the cold outer regions of a disk, sulfur is expected to reside almost entirely in solid particles rather than in free-floating gas.

A planet formed primarily from collapsing gas should retain near-stellar sulfur levels; a planet that incorporated substantial solid material should show clear enrichment.

The HR 8799 planets show enhanced sulfur, and the degree of sulfur enrichment broadly matches that of carbon and oxygen, suggesting that solid material played a decisive role in building these massive modies.

Implications for Massive Planets

Jupiter and Saturn exhibit similar enrichment in heavy elements relative to the Sun, a signature generally associated with core accretion. The new results indicate that comparable processes can operate in planets several times Jupiter’s mass and at much greater distances from their star.

The study estimates that the four HR 8799 planets together contain roughly 600 Earth masses of heavy elements, implying a substantial reservoir of solids in the system’s protoplanetary disk.

Whether the planets formed in place or migrated remains uncertain. However, their shared chemical pattern suggests a common formation history—one built from solid material before gas.