Why is there no water on Venus? New study has an explanation

A new study explains what happened to the water that once existed on Venus and what could happen to other planets in the galaxy.

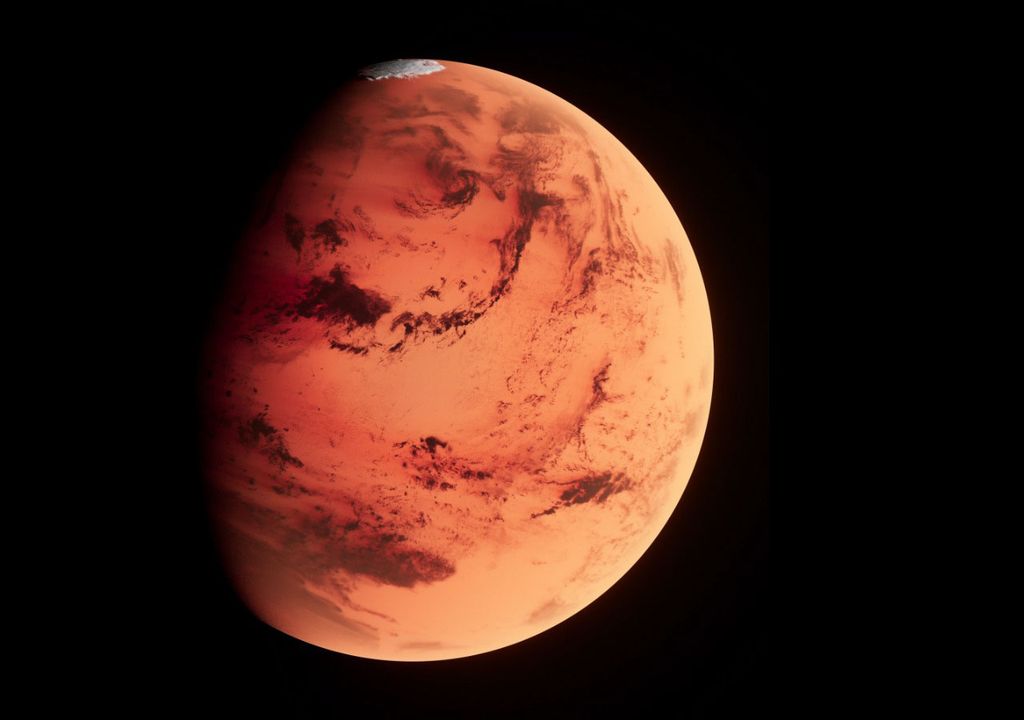

Venus is the Earth’s extremely hot and inhospitable neighbour, but it wasn’t always like that. Venus once had water, and a new study sheds light on how the planet became so dry.

Planetary scientists at the University of Colorado Boulder found an elusive molecule could explain “the water story on Venus” with their result providing an insight into what happens to water in a host of planets across the galaxy.

Escaping hydrogen

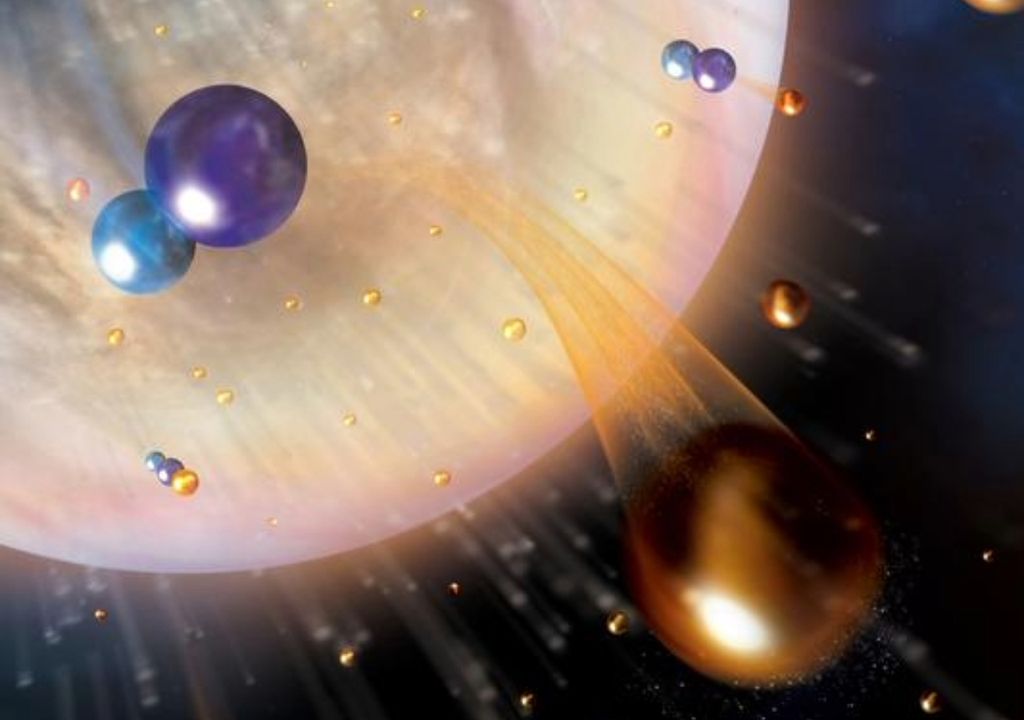

Computer simulations revealed hydrogen atoms in the planet’s atmosphere disappear into space through a process known as “dissociative recombination”; this caused Venus to lose almost twice as much water daily compared to previous estimates.

“Water is really important for life,” says Eryn Cangi, a research scientist at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP). “We need to understand the conditions that support liquid water in the universe, and that may have produced the very dry state of Venus today.”

Cangi says Venus “is positively parched”: if all the water on Earth was evenly spread over the planet, the liquid layer would be around 3km deep, but on Venus, where the water is trapped in the air, the layer would be just 3cm.

“Venus has 100,000 times less water than the Earth, even though it’s basically the same size and mass,” adds Michael Chaffin, research scientist at LASP.

History of Venus

Computer models enabled researchers to understand Venus as a gigantic chemistry lab focused on the diverse reactions within the planet’s atmosphere. The team found HCO+ high in the planet’s atmosphere may be behind the planet’s disappearing water.

This may explain why Venus – which probably once looked almost identical to Earth – is all but unrecognizable today, explains Cangi: “We’re trying to figure out what little changes occurred on each planet to drive them into these vastly different states.”

Its thought Venus once had as much water as Earth, but at some point, the CO2 clouds in Venus’ atmosphere initiated a powerful greenhouse effect in the solar system. This raised temperatures at the surface to over 480°C and all of Venus’ water evaporated into space.

But that doesn’t explain why Venus is as parched as it is today, or how it continues to lose water to space. Chaffin says: “As an analogy, say I dumped out the water in my water bottle. There would still be a few droplets left.” But on Venus, nearly all the remaining drops also disappeared – likely because of the elusive HCO+.

Mission to Venus

In planetary upper atmospheres, water mixes with CO2 to form HCO+. On Venus, HCO+ is constantly produced in the atmosphere, but doesn’t survive for long because electrons in the atmosphere find it and recombine to split the ions in two, leaving hydrogen to escape into space.

The new study indicates that Venus’ dry state can only be explained by a larger number of HCO+ in its atmosphere than expected: “One of the surprising conclusions of this work is that HCO+ should actually be among the most abundant ions in the Venus atmosphere,” Chaffin says.

But there’s a twist: scientists haven’t observed HCO+ around Venus, likely because few spacecraft have visited the planet and those that have lacked the instruments to properly look. NASA’s Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging (DAVINCI) mission will send a probe through the planet’s atmosphere to the surface, and while it won’t be able to detect HCO+, a future mission might.

“There haven’t been many missions to Venus,” Cangi says. “But newly planned missions will leverage decades of collective experience and a flourishing interest in Venus to explore the extremes of planetary atmospheres, evolution and habitability.”

News reference

Chaffin, M.S., Cangi, E.M., Gregory, B.S. et al. (2024), Venus water loss is dominated by HCO+ dissociative recombination. Nature