If space extends in all directions, what is beneath the Earth?

Is there a turtle holding four elephants on which the Earth rests? Or perhaps it is a huge Titan carrying the entire planet on his shoulders? Here we explain it.

Not long ago, I was reading one of those articles that appear on Facebook, where the main image was an upside-down world map. An initiative that has long been promoted by the people of Argentina, proposing that the North be the South.

Beyond the implications behind this idea, I started thinking about the astronomical reason why we choose the North to be up and the South down. In other words, when was it decided that orientation should be that way?

Researching a little online, I found that the most accepted answer is thanks to a convention used by ancient European navigators and merchants, finally established when the Mercator map was designed.

A reason with a bit more science behind it could be that for just under 13,000 years, a star has almost perfectly aligned with the Earth's rotation axis: Polaris in the constellation of Ursa Minor, marking what we know as the Celestial North Pole.

In other words, our “North Star” has been around long enough for us to use it as a reference for navigation or orientation across the nearly 68 per cent of the Earth’s mass that exists on this side of the equator. Very well, but then, what is beneath the Earth?

Down or up?

Except for a more or less dark period regarding science, and I say “more or less” because according to some defenders of the Middle Ages, there were indeed some advances, especially empirical ones related to medicine. At that time, it was believed that the Earth was flat.

The image many of us were shown in basic education was of a disc supported by elephants, which in turn stood on a turtle. A very different image from that of the Titan Atlas, who held a globe on his shoulders for eternity, according to the Greeks several centuries earlier.

In these images, it was relatively easy to identify where “down” was. Taking this as the floor, where the turtle or Titan stood, and that was it. However, by the Renaissance, the questions arose again: How do we verify the sphericity of the Earth? What is beneath us?

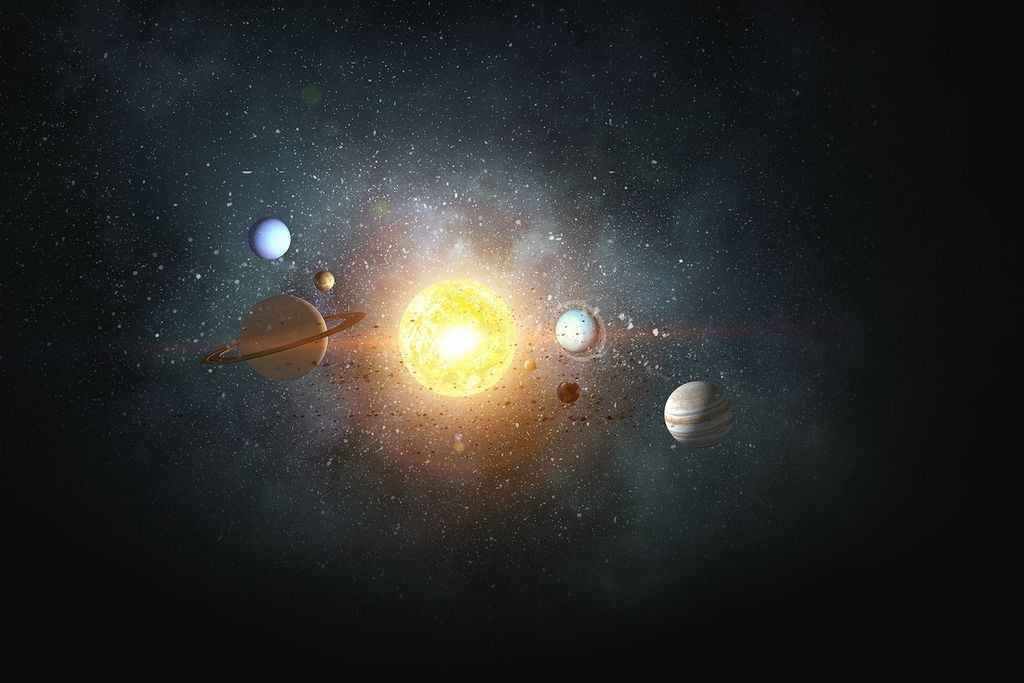

In the strict sense of the question, beneath us is the centre of the Earth, and that is it. Let us continue observing the stars! But why stop here and not keep exploring what lies beyond, on the other side of the planet, beneath the Solar System? Is it even possible to pose this question?

Up or down?

A very beautiful phrase that my postgraduate tutor, Dr Deborah Dultzin, left me regarding astronomical observations and measurements is the following:

Let us think about what she meant by that. Since the conventions of “up” and “down” only work when we have a frame of reference, if one day we find ourselves lost in space, we will not be able to answer so easily. Thank you, astronomers!

When we observe through a telescope, due to the optical path that light follows as it passes through or reflects off lenses and mirrors in our instrument, directions inevitably change, and what from our perspective is down or to the right will appear up and to the left.

In astronomy, we usually solve this problem very simply. We establish a fixed reference point for any observer on Earth, and from there, depending on the direction we are looking, we assign values as positive or negative.

In general, movements are on a large sphere, so using mathematical conventions, anything moving counterclockwise is taken as positive, in the same way that movement from the Equator (down) to the North Pole (up) also has the same sign.

No privileges in the universe

In previous entries, we have discussed the conservation of angular momentum, that physics principle which makes spinning objects rotate faster if they are short or slower if they are long, like the arms and legs or skirts of ballet dancers.

This also happens when a star is forming, as we discussed in the article on Herbig-Haro objects, but what determines the direction of rotation? That we do not know. Any small perturbation or external stellar wind can make it spin in any direction. There are no privileges in the Universe.

What is intriguing in the Solar System is that most planets rotate in the same direction, if we view them from “above,” or perpendicular to the ecliptic, from the celestial north. Except for Venus and Uranus, which are believed to have suffered major impacts, most rotate counterclockwise (to the left).

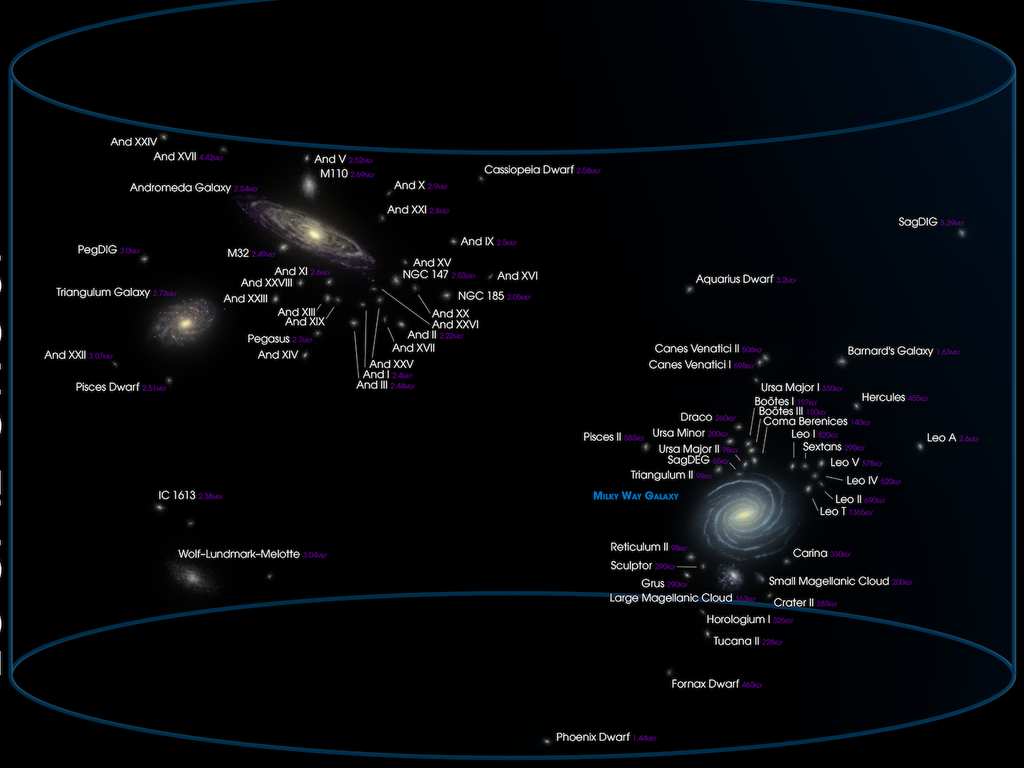

If we go further, we find the galactic plane, to which we also assign a north and a south that, for convenience, almost perfectly coincide with our previously assigned points.

So… what is beneath? The only thing we can answer with certainty is: “It’s full of stars!”